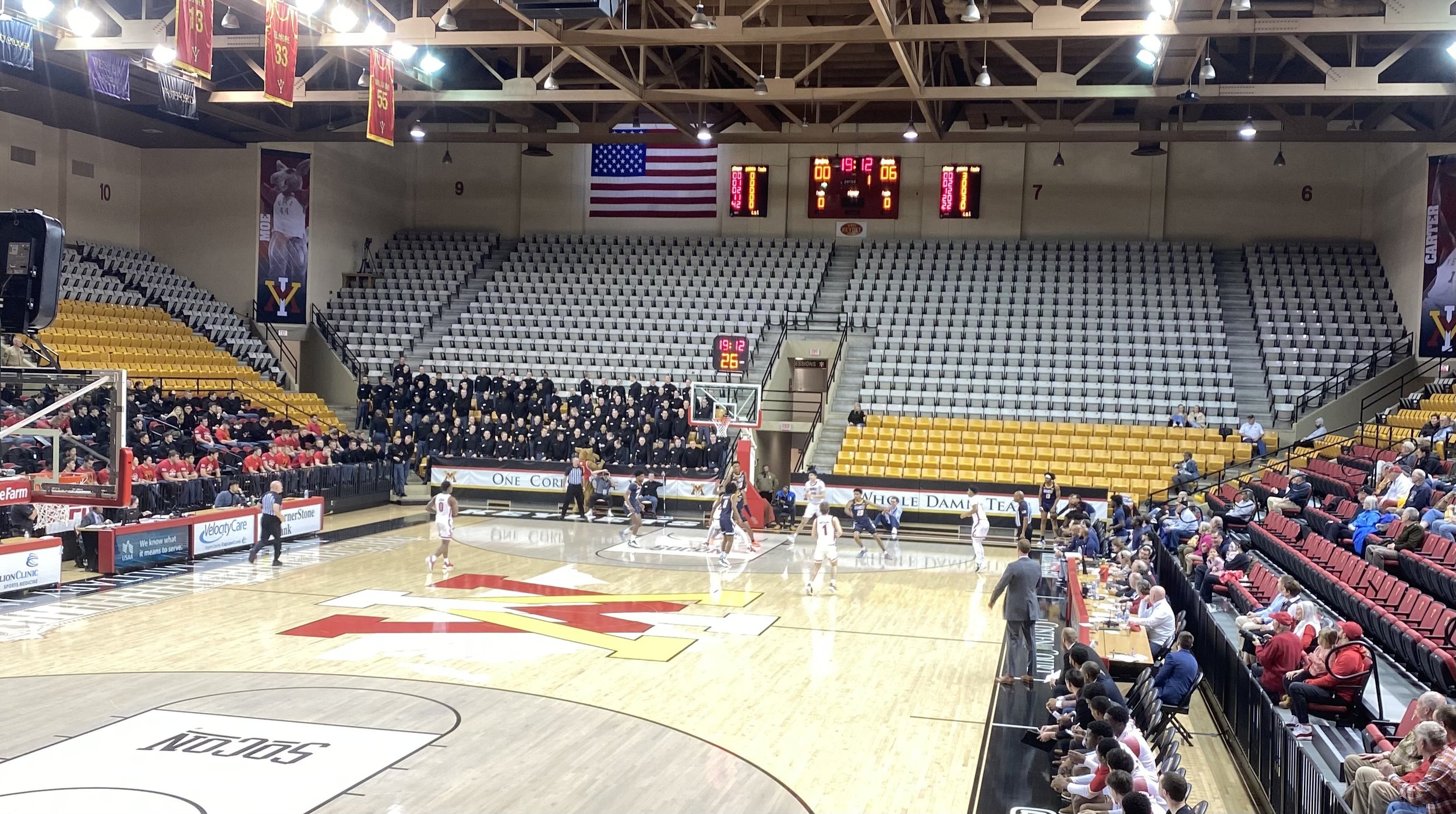

(Photo Courtesy of Jack Hunter)

Eller, a former VMI linebacker from Roanoke, says the school’s athletic programs lacked the “bare minimum” with no nutritionists.

“Guys are eating a bowl of cereal for dinner after a practice, and it's like you can't really expect our guys to go out and perform and develop when they eat a bowl of cereal or just a small salad from the salad bar for dinner,” he said.

Marcello said Head Football Coach Danny Rocco was unavailable for an interview.

Josh Knapp, a defensive back, says players often eat at local fast-food restaurants like Cook Out.

“It's hard to operate as a Division I football player when you're struggling to get the proper amount of food that you need to perform after a long day of practicing workouts,” said Knapp, whose only D-I offer out of high school in Abingdon, Md., came from VMI.

Lack of resources

VMI football transfer Evan Eller says there is a lack of nutritional resources available to VMI football players. (Photo courtesy of Evan Eller)

In his junior year, Eller tried to get out of VMI. But he didn’t transfer at that point because he only got offers from smaller D-I schools.

“I’m only two semesters away from graduating,” he said.

Eller graduated a semester early and used his extra year of eligibility so he could play while he’s in grad school at the University of Wyoming, where he says the athletics facilities are nicer than VMI’s.

He says a big difference between Wyoming and VMI is the time he can devote to developing his skills as a football player. “I spent three hours at the football facilities between lifting meetings and practice at VMI a day, and that's like maximum. At Wyoming, I'm spending six, seven hours at the facility,” he said.

Wyoming’s athletics program provides Eller with a larger weight room, scheduled recovery time, a cafeteria exclusively dedicated to athletes and a nutritionist who designs custom meal plans for him.

Compared to other D-I schools, Eller says, VMI’s weight room lacks in equipment and amenities. (Photo courtesy of Carly Snyder)

Knapp also saved his extra year of eligibility for grad school.

“VMI is such a hard place and when I already got … two and a half years of it done, it was like, I might as well just keep going,” he said.

Knapp says he realized that there’s a bonus to attending a larger D-I athletic program. That’s the opportunity for athletes to negotiate so-called NIL deals to capitalize financially on their name, image and likeness.

“No one really wants a VMI football player to rep their brand just because we're not really as known,” he said.

Initially, Jacksonville State University accepted Knapp to play football, and he soon realized that he could make money receiving monthly NIL payments.

VMI football transfer Josh Knapp, a defensive back, speaks about the living conditions VMI athletes encounter compared to other D-I schools. (Photo courtesy of Josh Knapp)

The NCAA reached a settlement with major conferences on May 23 that would allow schools to pay athletes directly, possibly starting in fall 2025. The proposed deal settled three antitrust cases that included nearly $2.8 billion in damages that will be distributed to current and former college athletes who sued over not being compensated for use of their name, image and likeness. A judge must approve the proposed settlement before it would go into effect.

"What [we] don’t know yet [is] exactly how this will all shake out,” Holy Cross Professor Victor Matheson, a sports economist, said in an email. “But this should allow smaller schools and/or conferences to decide to pay players if they so choose. My guess is that most of the smaller conferences will choose to not make player payments beyond scholarship money."

VMI’s athletics program is not just losing players. It is losing money, too. The military school’s athletics budget fell short by nearly $1.9 million in 2023.

From 2018 to 2021, VMI’s athletics program covered expenses with a little money left over. But in fiscal years 2022 and 2023, the athletics department began to lose a lot of money. In 2022, VMI showed a loss of $445,000.

The football and basketball programs are both operating at losses, according to VMI’s 2023 financial report. Football lost $1.1 million, and basketball nearly $777,000.

Butler also says he believes NIL is a game-changer for college athletics.

“It's not college basketball anymore. It's becoming more of a business,” he said. “You're not really looking for a home. You’re looking for the place that can pay you the most money.”

In 2023, VMI’s athletics programs operated at a loss of nearly $1.9 million. Source: VMI’s Agreed Upon Procedures Report, 2018-2023

Aid provided to student-athletes has increased by roughly $1.5 million since 2018. Source: VMI’s Agreed Upon Procedures Report, 2018-2023

Since 2018, VMI’s expenses have ballooned by nearly $4 million, while revenues have only increased by roughly $2 million.

Ticket sales for sporting events are not a solution for VMI. All sports, except football and basketball, brought in a total of $1,020 in 2023. Football and basketball brought in $309,000 and $40,800, respectively, in ticket sales in 2023.

VMI spent $2.7 million in “athletics student aid” for the football program in 2023—nearly half the athletics department scholarship budget. The school spent $750,000 last year on aid for basketball players.

The military school spent $3.1 million on coaches’ salaries and bonuses last year. The football program’s staff members were paid nearly $1.2 million, while the basketball coaches earned $650,000. Coaches in all other sports received $1.3 million in salaries and bonuses.